The Merchant Empire of the Sogdians

-Judith A. Lerner

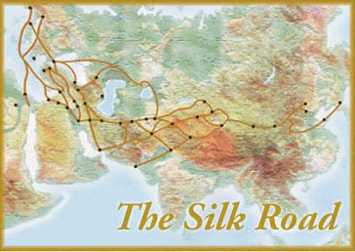

Judith’s opening quote, “Men of Sogdiana have gone wherever profit is to be found” outlines the consensus of her piece. I feel that every reference she makes in The Merchant Empire of the Sogdians agrees to this statement. The 4th and 7th centuries marked the activities of the merchants mainly from the Sogdian’s, Iranian people from Central Asia. The Sogdian’s were constantly exposed to domination factors through the leadership of princes, powerful leaders and the domination of the nomads, the Turks. It is questionable whether the Sogdian’s were embedded in a feudal system or not. Lerner states that the Sogdian’s followed the feudal system but Marshak clearly states that the system was not feudal. In, Sogdians and their Homeland, Marshak states that merchants were positioned between the nobility and the working class based on their social and political significance. This idea makes more sense to me because it provides an explanation to the drive of the people of Sogdiana to accumulate profit. The greater the success the higher they are ranked. If it were a feudal system that they were immersed in, than it would not matter how much wealth they accumulate because the feudal system is based on one’s inheritance. This would not spark a large interest in the act of achieving one’s own wealth. The Sogdian’s exposure to domination must therefore lead to their desire for power. The Sogdian’s sought power in the accumulation of profit and wealth. The main source of economy for the Sogdian’s was agriculture. When agricultural trade did not generate as much wealth as they desired, the Sogdian’s used their geographical location to their advantage and made use of the rivers, the Amu Darya and the Syr Darya which allowed them to travel along in Silk Road practicing trade. It was interesting to read that from a young age, more specifically at age 5, a young boy is expected to read books and as he understand them, study commerce. This proves that at a young age, men in Sogdiana are exposed to the world of trade and profit. Children are taught at an early age to desire potential earnings from trade. The Sogdian’s therefore held superiority on the Silk Road because their society was deeply embedded in reliance to profit and money. Since trade allowed the Sogdian’s to interact with many different peoples, societies and cultures, they were exposed to many different and unfamiliar languages. The language barrier interfered with trading goods which therefore affects the amount of profit being consumed. In order to eliminate this problem, the Sogdian’s learned the Buddhist language and were able to translate Buddhist texts. This gave rise to another source of income, the translation of Buddhist texts. Sogdian’s learned how to trade efficiently and broke down many barriers they faced in order to trade with every culture. I believe that their ability to override each obstacle proves they were intellectual people whom educated themselves in the field of commerce and trade. The Sogdian’s allows for many new ideas to spread along the Silk Road. Referencing back to the quote Lerner opened with, the basis of Sogdian society was to attain a sufficient amount of profit. The Sogdian’s travelled along the rivers; embedded commerce into the education of young boy’s and broke down language barriers all in aim of acquiring capital. Men of this culture oriented their lives in order to achieve this one goal.